(Who Isn't) On the Radio

(Fall, 2025)

Before continuing, note that the following is based on data collected in 2019 and may not be an accurate picture of the current state of classical radio programming at these stations today. This is a dormant (not dead!) project, but one we hope to return to it soon. As it is, the data serve as a record of classical radio in 2019, and anecdotally speaking probably speaks to the current state of things.

Introduction

This project began with a fairly straightforward question: How does programming on American classical radio break down along gender lines for composers heard over the airwaves?

This page is one part of a larger collaborative effort initiated and conducted by Jacques Dupuis and Kathryn Dupuis. We hope this data sheds some light on broader trends in classical radio programming, which is by some measures the most common mode of encounter the average person has with classical radio on a daily basis. It is also one that has generally been given almost no extended scholarly consideration that we know of (if you do know of similar projects, please email Jacques at jdupuis42 AT gmail DOT com, or reach out via his Twitter, linked in the menu bar above).

The following graphs reflect data collected from two time frames in 2019: February 1–April 10 and July 21–September 27. The stations included in this data are:

- KDFC (San Francisco)

- KING (Seattle)

- KMFA (Austin)

- KPAC (San Antonio)

- KSJN (Minneapolis/St. Paul)

- KUSC (Los Angeles)

- KWMU (St. Louis)

- WCRB (Boston)

- WETA (Washington, D.C.)

- WFMT (Chicago)

- WIAA (Interlochen, MI)

- WKAR (Lansing, MI)

- WQXR (New York City)

- WRTI (Philadelphia)

- WSHU (Connecticut/Long Island)

This data was originally presented in 2019 as a paper at the University of Texas at Austin Musicology Conference and poster at the American Musicological Society’s national meeting in Boston, Massachusetts. We are currently in the process of gathering more current data and adjusting the automated web scraper used to collect this data to account for changes in websites and holes in data created by those changes.

Below you will find:

- a series of images with graphs and tables depicting the data gathered in October 2019

- a simplified technical explanation of the programs written by Kathryn

- a set of caveats that will undergo revision as the project progresses

- a closing commentary on the broader implications of this project

Graphs of Data

Please forgive the temporary use of images rather than embedded graphs and tables. These will be replaced with more accessible presentation soon that will work for screen readers. All images my be expanded by opening the image in a new tab or window.

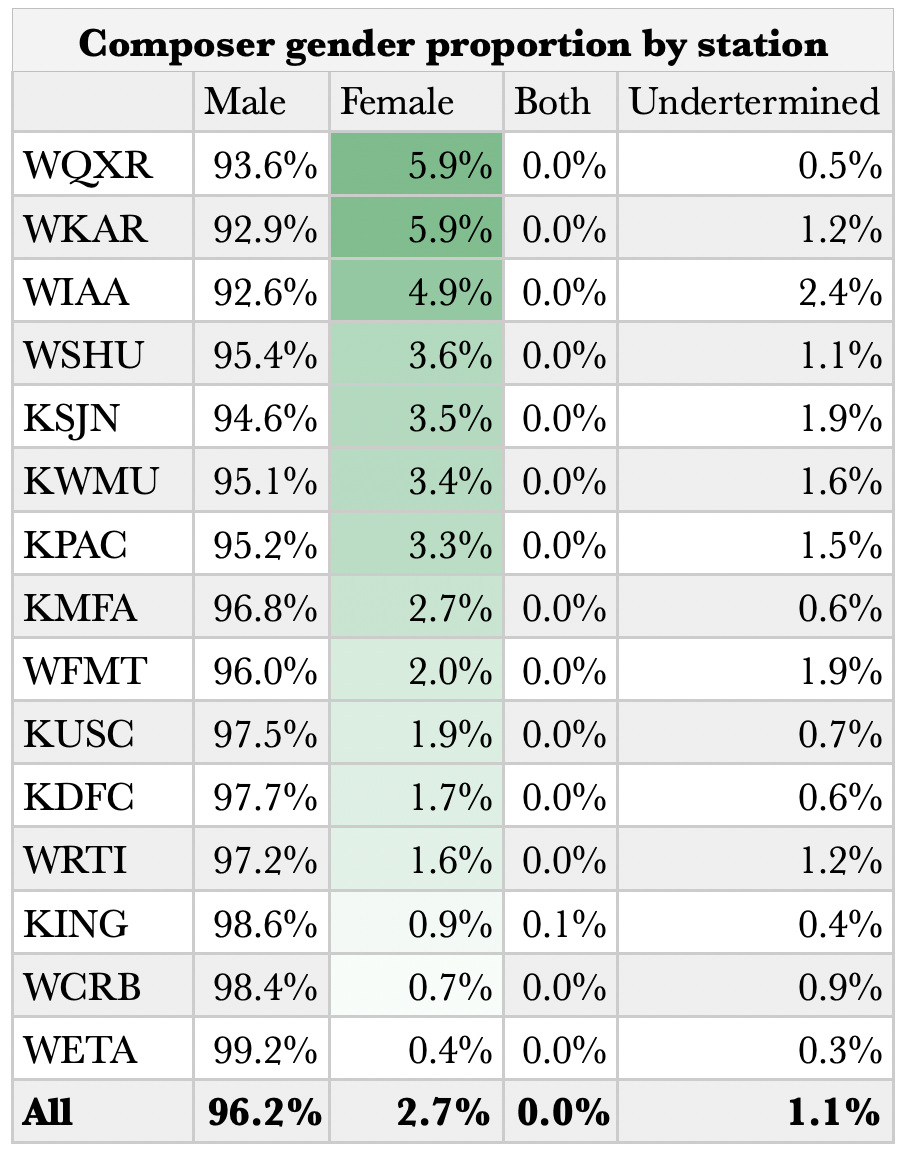

These are the percentages of male and female composers across all stations in our sample set, as well as percentages for music written by at least one man and one woman, as well as anonymously composed music.

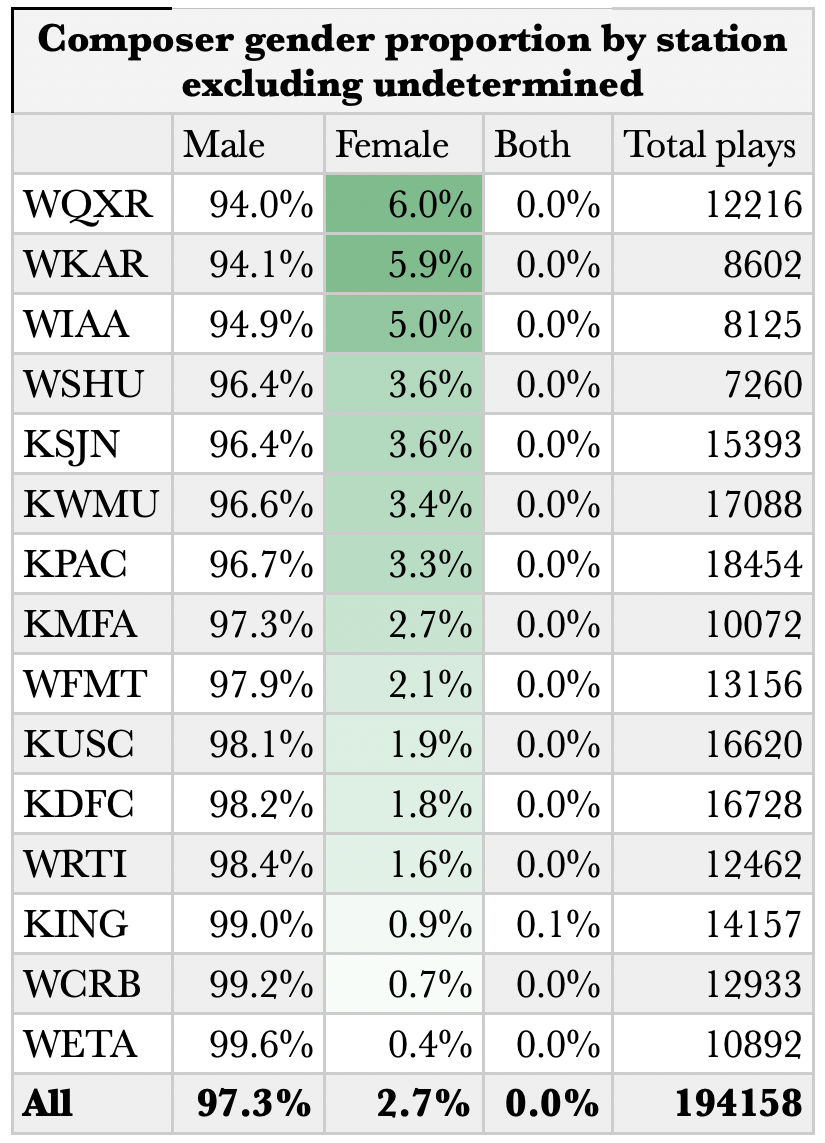

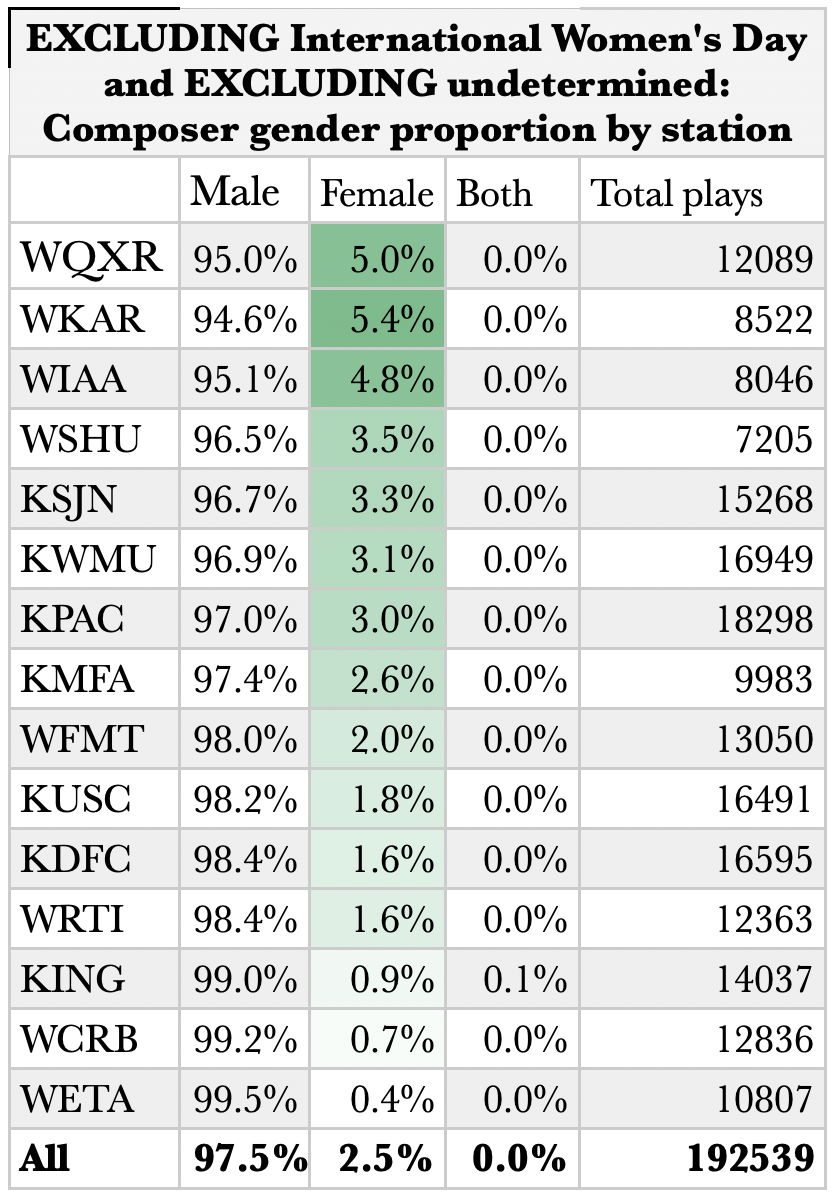

Here is the same data, minus music by undetermined composer.

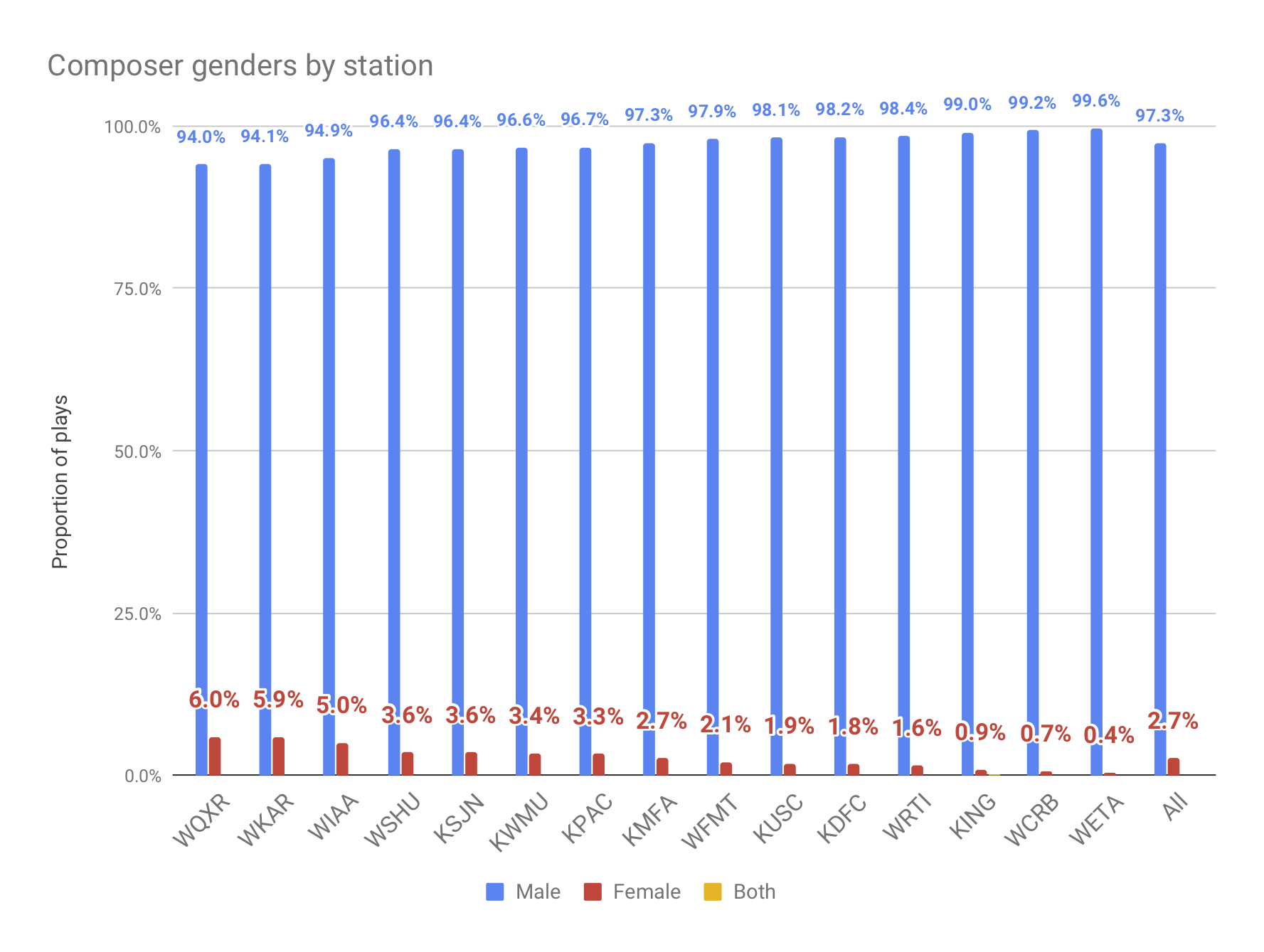

Here is a somewhat starker portrayal of the same data, using bar graphs to highlight the disparity.

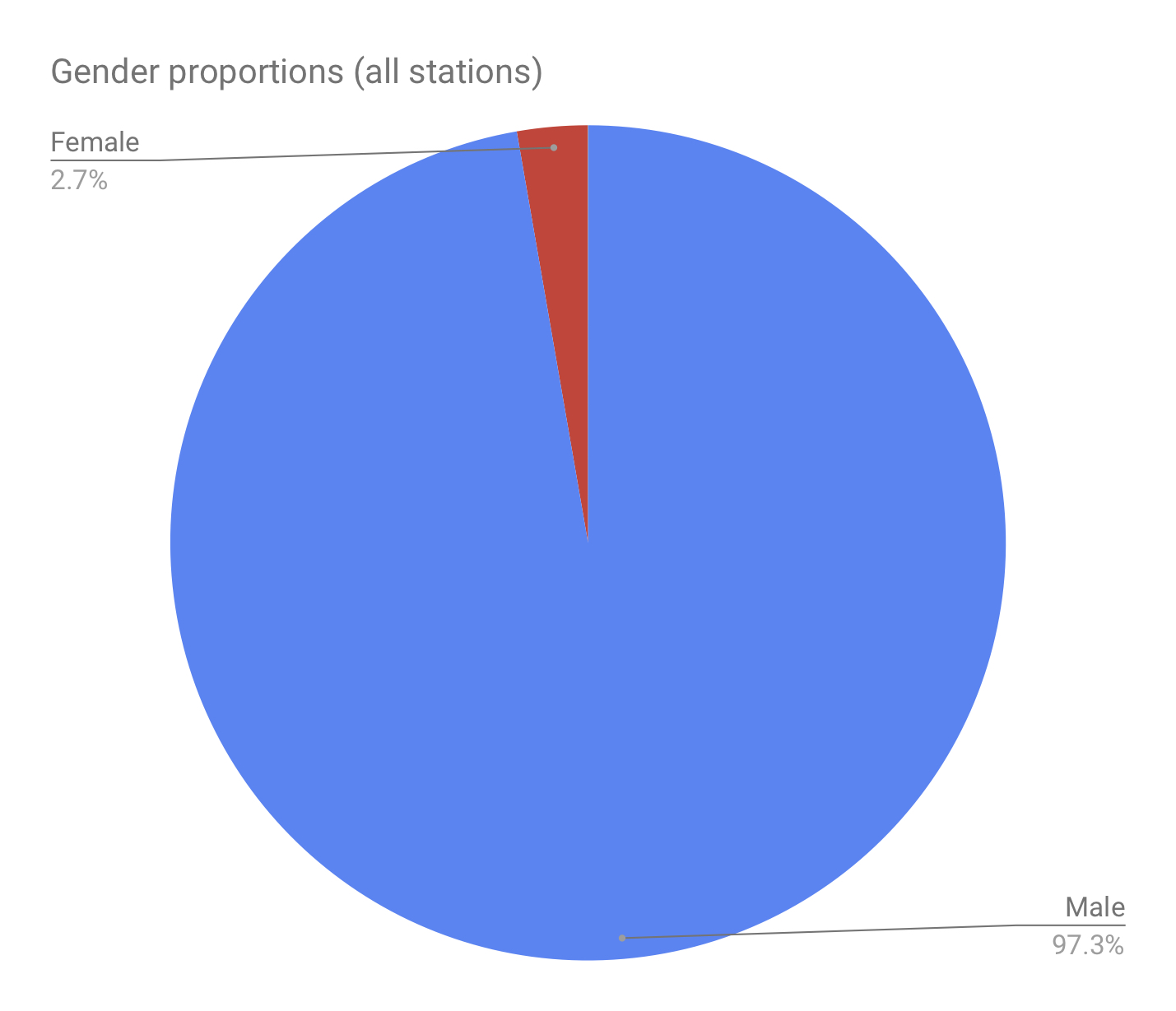

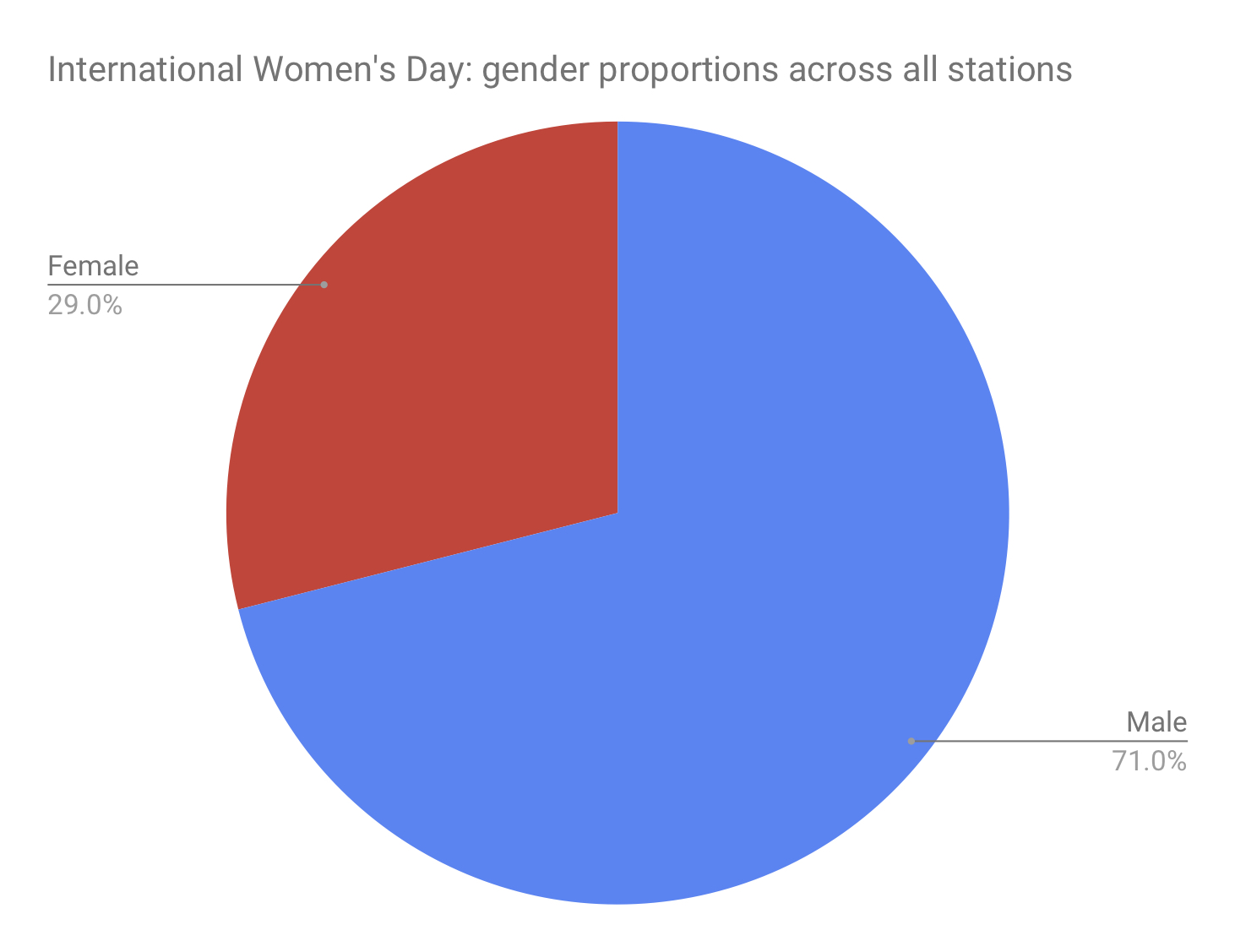

And a pie graph representing the same.

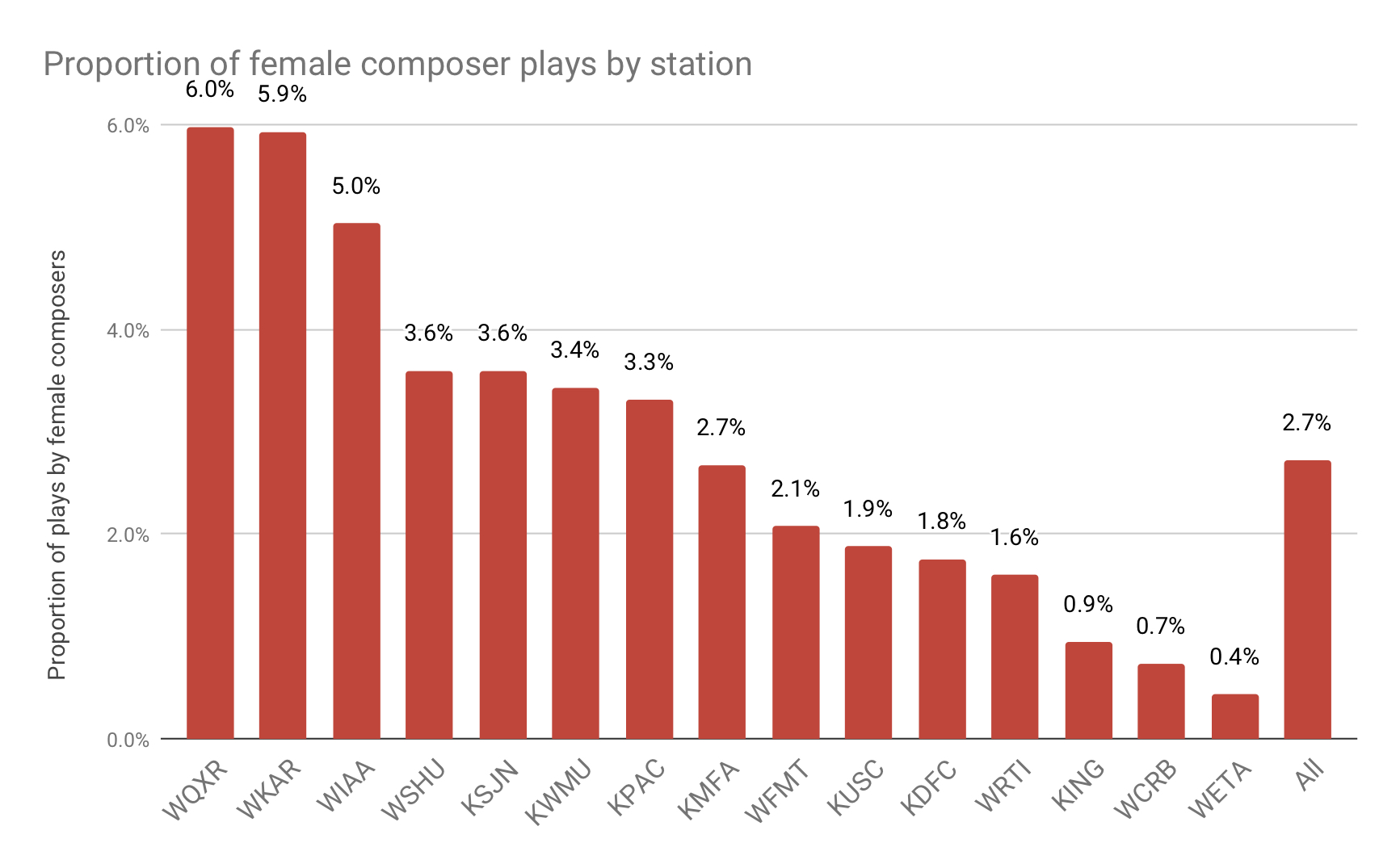

And here is a comparison of the stations against one another in terms of percentage of female composers played by each.

International Women’s Day

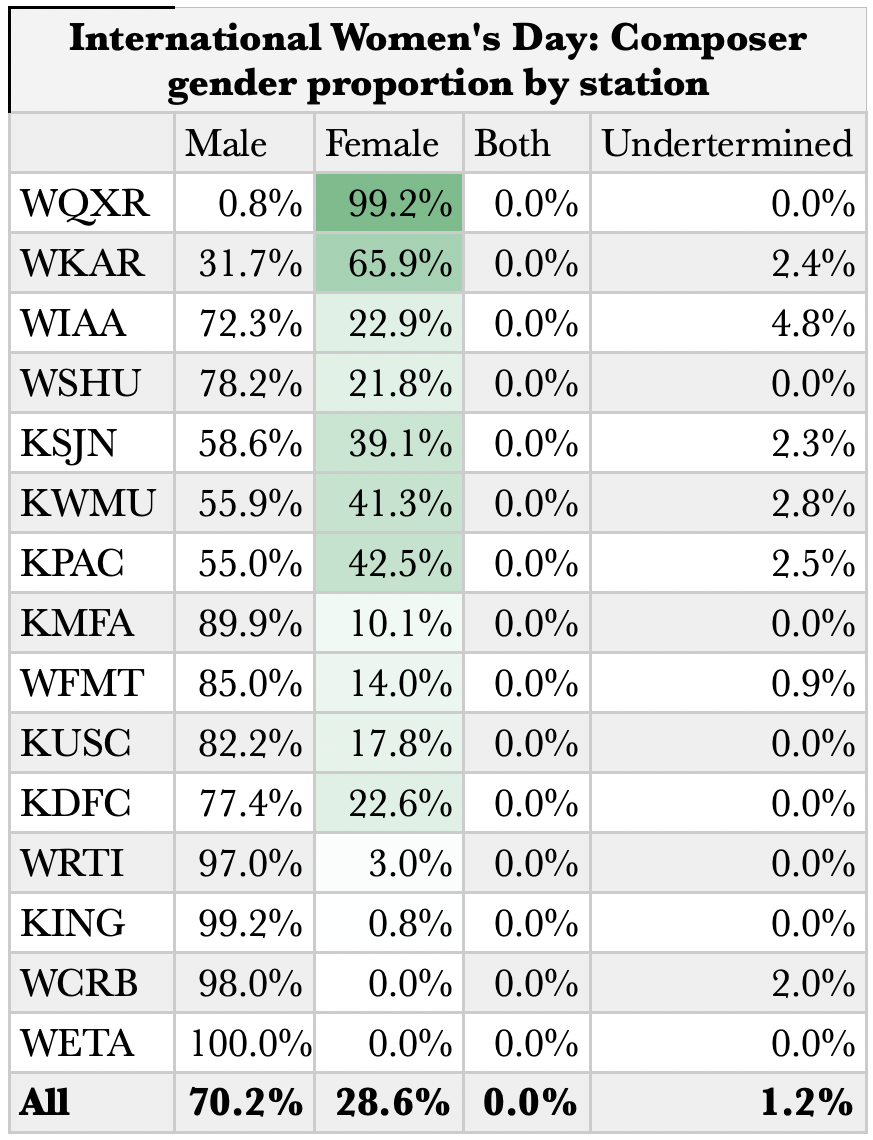

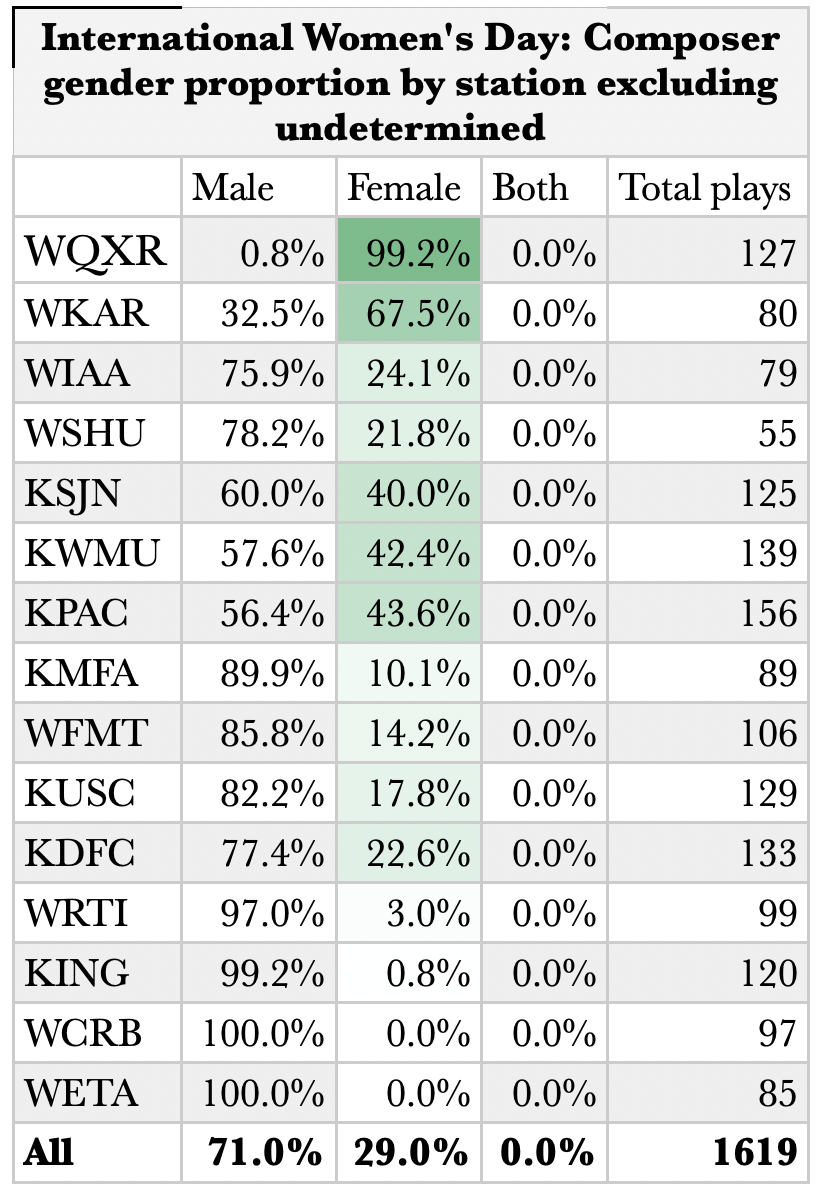

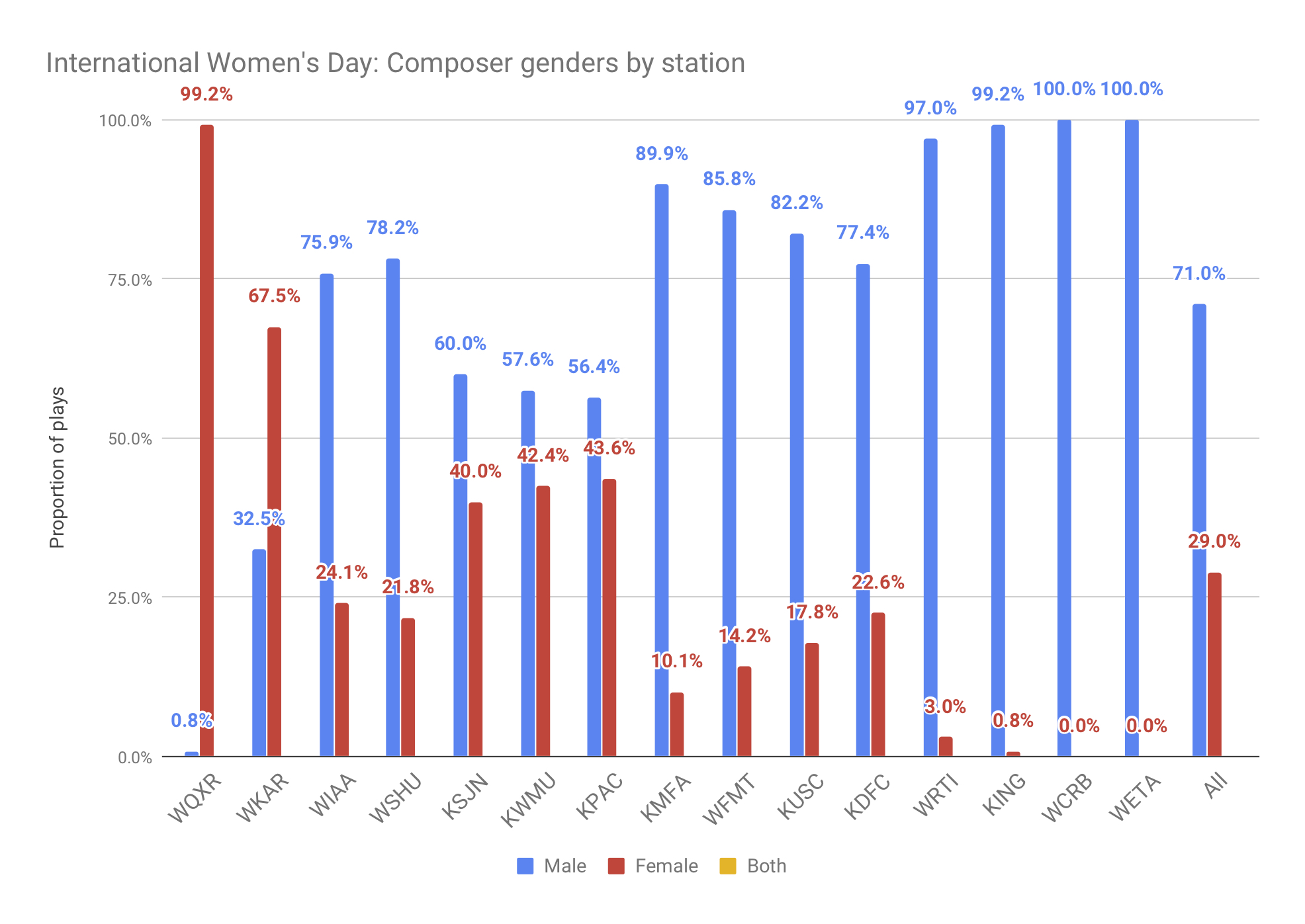

International Women’s Day inevitably presents stations with a cause for increasing the airplay of women composers. Of note, not all stations take this opportunity, and with the exception of WQXR in New York City and WKAR in Lansing, Michigan, none broke even. WCRB in Boston and WETA in Washington, D.C. did not register the day, nor, it seems, did KING in Seattle.

Overall, however, the percentage of composers played who are women increased significantly to 29%.

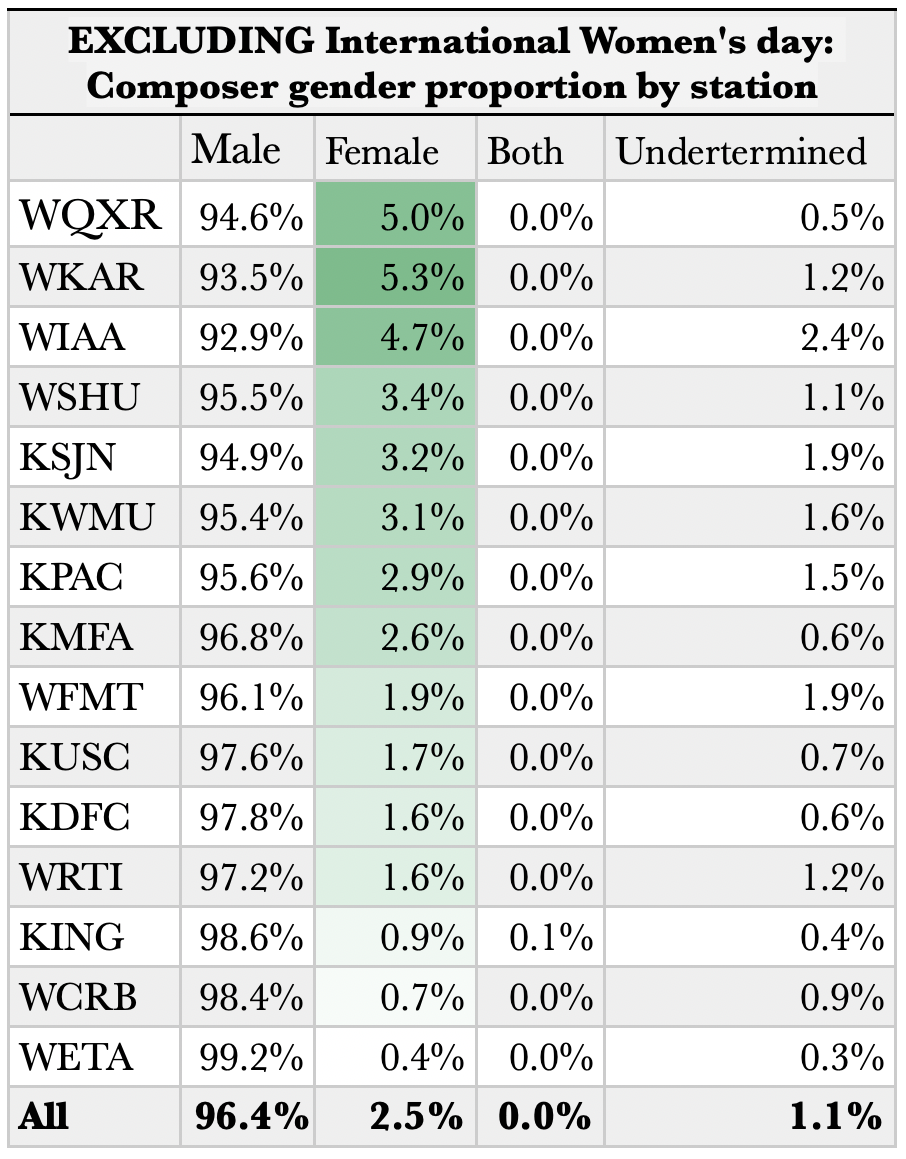

Controlling for the anomaly of International Women’s Day, the overall picture across our time frame becomes even starker than what we see in the first graphs on this page.

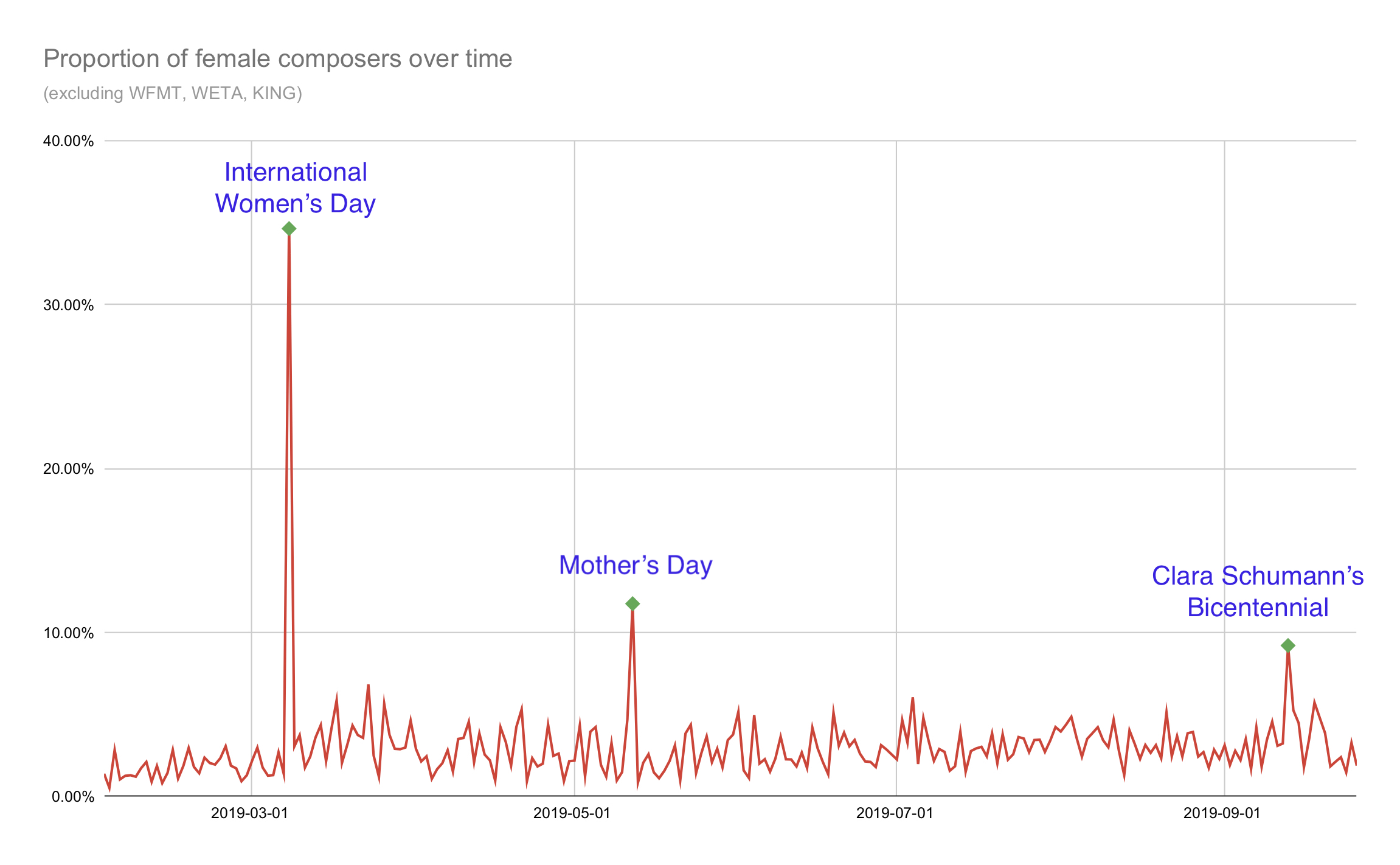

To reinforce the point, here is a line graph of the statistics across the better part of 2019. Anomalous days that year included IWD, Mother’s Day, and Clara Schumann’s bicentennial. (Note: WFMT, WETA and KING were removed because of gaps in the data we were able to scrape for those stations.)

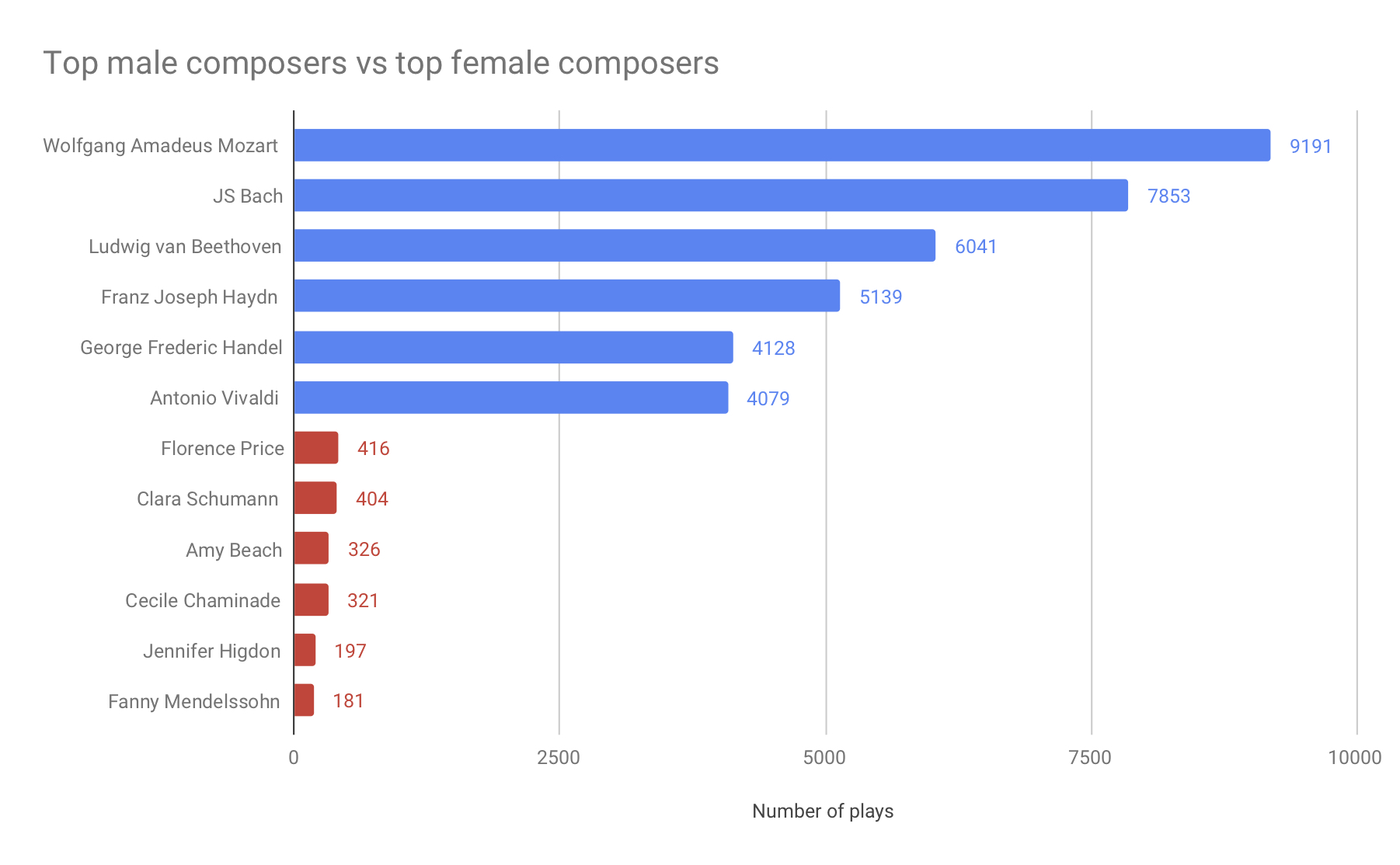

Finally, to compare on a more granular level, here are the pure numbers of plays the top six male composers received in our data compared against the top six female composers.

Technical Explanation

To obtain the data for this project Kathryn developed a Python script that employs two methods of data extraction: scraping radio websites (for example WQXR), and fetching structured data from radio sites’ APIs (for example WRTI). The program is designed in a modular way to support easily adding new stations. Each station has a configuration module that specifies the URL, and where in the webpage or structured data to find the playlist information. This modularity allows the developer to avoid rewriting for each station the webpage or API fetch, the data extraction and normalization, and the output file writing, since those functions are all performed in code shared by the station modules. For stations where website scraping is used, CSS selectors in the station configuration indicate where on the web page to find playlist items and information about those items. The program uses an open source python library called BeautifulSoup to extract data from the websites based on the CSS selectors configured for the station. For stations where APIs are used to access playlist data, the station configuration specifies JSONPath selectors to indicate where in the structured API data to find the playlist items and item data. The program uses another open source python library, called JsonPathNg, to select information from the API data using the JSONPath selectors. It appears these APIs were mainly intended to service the radio stations’ web pages themselves, rather than as a method for developers to fetch structured data from web pages for research such as this, but access to the APIs is not limited. This has made the extraction of data for the stations where it is available much less labor-intensive. The program exports a CSV of the data it extracts, which we loaded into BigQuery table. Unique composer names were extracted to a spreadsheet, where we manually marked the genders of each. The labeled composers were then uploaded to BigQuery in their own table, and the dataset of plays is joined with the labeled composers to get a table of labeled plays. The fully labeled data is then exported to sheets to build charts and graphs. In the future we may use a visualization tool that reads directly from BigQuery, such as Data Studio or Tableau. One challenge was that many composers are spelled (or misspelled) many different ways, and each variation had to be marked separately. Other challenges were more technical. We were not able to extract data for some radio stations because the site’s HTML did not mark where each piece of necessary information was located, and there was no API available. For the most part, each site that we could extract from required manual work to identify where on the page to find the information, and code this into a site configuration. And some radio stations listed the same piece twice for a single play of the piece, for example when a play crossed from one day into the next. These had to be deduplicated in the program.

Caveats

This methodology and data carry a number of caveats, restrictions and limitations, which need stating. The first is data set boundaries. Per the title of this presentation, this is a survey only of classical radio stations in the United States from a wide geographical area but focused in metropolitan areas selected from Nielsen’s top radio markets by population. Only stations technically possible to analyze are used, with the number of stations studied currently standing at fifteen.

A second caveat is that, as is often noted in studies of representation and gender, the present study does not give the full picture of the issue, only one facet, an added data point; the complexities and nuances of gender and sex are reduced here to male or female. In manually coding composers by sex, we did not encounter any cases that required we make a decision with regard to non-binary or gender queer composers. The only trans composer encountered is Wendy Carlos, whose pronouns are she/her, enabling definitive coding in this case. That this was not an obstacle that arose is, we would argue, an issue worth considering on its own. This is also a study only of gender, and does not encompass racial, ethnic or cultural heritage identities.

Limitations also exist in the sourced playlist logs. Programming includes not only music, but also syndicated features like American Public Media’s “Composers’ Datebook,” news, station updates, fundraising drives, weather and other such segments. Unfortunately, the scraper cannot pick up special programs, like live rebroadcasts or transmissions of classical music concerts, and some regular programs may not be music at all (for example, one station broadcasts comedy shows). When composers are not listed, or where composers are anonymous, as for folk music and early music, items are coded in their own category.

Finally, regular programming at various stations is managed through syndication of services like Classical24, produced by American Public Media and Public Radio International. This reduces the number of people responsible for programming, which somewhat skews a view of how the data is generated, and several stations will have duplicate programming. But the underlying question remains: What do people hear on the radio? In our view, each station that syndicates regular programming chooses to syndicate, and thus endorses what is played. To be more blunt, syndication does not reduce responsibility and represents only a difference of mode in decision making, and it is this interpretation that we have chosen and these type of plays are counted as unique. The statistics reflect what was heard over the airwaves, not simply how many decisions by individuals were made.

Closing Commentary

We see a number of potential next steps for this project, including ongoing updates to the data, expansion to new radio stations (and even countries), and expansion beyond composers to performers, including conductors and soloists. In technical aspects, greater data capture can be facilitated by incorporating the Google Knowledge Base Search API (part of the tool set that gives us the knowledge cards that appear as quick results in Google searches). We also plan to find more granular approaches to the data, like considering whether individual pieces are played more than others, and judging whether this reflects any trend in who is played. Similarly, we are working on isolating particular times of day (drive time, day time, nights, weekends, etc.). Generally speaking, the next steps involve more trend-oriented information.

The biggest underlying question of this study is why things are the way they are, for which there are a number of speculative answers rooted in related issues like industry decision-making and cultural status quo. Market-driven approaches to programming draw on audience preferences and long-term commercial results for stations, which are, of course, businesses, averse to the bottom-line risk that adventurous or unfamiliar programming presents. Similar considerations are in common with performing ensembles, shown, for instance, in models of programming that join non-canonical composers or pieces to canonical ones to draw audiences to the familiar while exposing them to the unfamiliar. In the case of radio, however, in examining what is played, this model fades when accounting for the high volume of non-canonical composers played who are not women or composers of color.