Women Vienna Honored

|

|---|

| via Europeana |

28 November 2021

The project I’m currently finishing an initial draft of is an essay for an upcoming edited collection on the Schumanns, and my contribution covers Clara’s honors and professional affiliations, coming out in the next couple years. I’ve been over-researching it a bit, because it’s led me down some interesting alleys and, as the editors said, these sorts of recognitions have little scholarly coverage. Not none, it’s just scattered and supports other studies, and there’s no dedicated study that I’ve found. One of those alleys has entailed trying to suss out what, for instance, honorary memberships signified, what they did for artist and institution, and who got them. Here are a couple of observations about that last issue.

Honored at the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde

During her well-documented, landmark 1837-38 concert tour/stay in Vienna, Clara Wieck received an honorary membership (the first of many) from the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (GdM)—now renowned, but struggling at the time and looking for ways to bolster its reputation through such honors. As I was looking through an institutional biography of the GdM written by Richard von Perger and Robert Hirschfeld (Vienna, 1912), I scanned the list of honorary members. Probably surprising no one, it’s…very male. But not just on the order of mostly male, more on the order of almost entirely male.

Who Got Honored?

Of the 135 honorary members that Perger and Hirschfeld list, only 9 were women, a mere 6.7%. That’s pretty startling, though again not surprising. Zooming in a little more, it’s even a bit more startling. The GdM was founded in 1812, had its charter statutes revised in 1814. After the first two women were inducted, it wasn’t until 1871 that another woman was named honorary member when three were. The rest named in the list were all inducted between then and 1898. (Many more have since been named.)

But who were they? Well, Clara Schumann was actually the second, named in 1838. The first was Maria Paulowna of Russia, Grand Duchess of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach (Мария Павловна; Paulowna is Perger/Hirschfeld’s transliteration), who was an amateur musician and early benefactor, named honorary member in 1814, the same year as the statutes revision. The full list of women named honorary members by 1912 include:

| Name | Date Named Honorary Member | Occupation |

|---|---|---|

| Maria Paulowna | 1814 | Amateur Musician/Patron |

| Clara Wieck (Schumann) | 1838 | Pianist |

| Karoline von Gomperz | 1871 | Singer |

| Luise Dustmann | 1871 | Singer, GdM Faculty |

| Marie Wilt | 1871 | Singer |

| Pauline Lucca | 1879 | Singer |

| Amalie Materna | 1888 | Singer |

| Pauline Metternich | 1892 | Patron |

| Anna Amadei | 1898 | Patron |

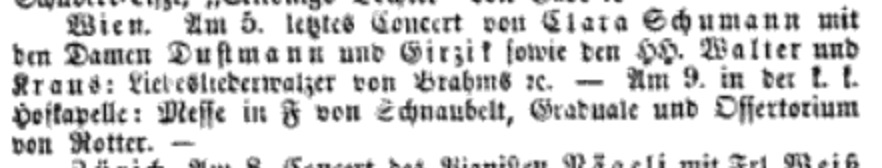

Amadei and Metternich were both arts patrons: Amadei’s son had attended the GdM’s conservatory, and Metternich was the granddaughter of the notorious Klemens, as well as a big supporter of Richard Wagner, purportedly the instigator of the notorious Paris Tannhäuser. The rest of the women in this list were established and/or widely-known singers of their day. Wilt and Dustmann were especially renowned. Clara Schumann even played with Dustmann not long before the latter’s induction as GdM honorary member. Dustmann also served on the faculty of the GdM’s conservatory.

Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, 21 January 1870

So What?

Scanning the 126 male honorary members of the GdM up to 1912, it’s a laundry list of textbook-famous composers and performers. There’s more to say about these institutions and honors in terms of their finer functions and roles (I’m going to leave my theorizing on this for publishing projects), but my working argument with these sorts of honors and the institutions is that they are yet another cog in The Canon’s machine. In the GdM, we have an institution that says that if you were a woman in 19th-century Europe, you could gain legitimacy as a vocalist or a patron. Clara, whose reputational legitimacy was freighted with masculinity, somewhat eschewed this restriction. That’s not to suggest she was not affected by patriarchal structures and practices—she obviously was—but her reputation and legacy are nuanced and complicated, and I think this particular situation shows some of that.

At this point, we don’t necessarily need more data points to confirm what we know about the kinds of careers women could carry in 19th-century German-speaking lands, but I’m a big believer that having more detailed data helps make air-tight what we know otherwise. Sometimes, the extra light shows just how stratified the situation is.